Moreover, the root causes of mental illnesses vary tremendously, from biological factors like body chemistry to the social determinants of health (economic status, culture and so forth) as well as the lasting impacts of early-life trauma.

Teasing apart these variables to effectively treat a patient is a significant challenge. But by taking a “biopsychosocial approach,” incorporating biological, psychological and social inquiry, Carleton University neuroscience researcher Robyn McQuaid is working toward the development of more personalized approaches to mental illness.

“Our lives — including the stressors we encounter — impact our biology, and our biology impacts our lives,” says McQuaid, whose department investigates health issues from the cellular to community level.

“It’s a circle, so we need to take a comprehensive approach. This can be tricky, but it’s important if we want to create more individualized treatments.”

McQuaid, who is also a scientist at The Royal’s Institute of Mental Health Research in Ottawa, collaborating on studies at the hospital, believes that we need to move beyond a one-size-fits-all mindset.

“We’re taking a trans-diagnostic approach, which means we’re looking across diagnoses at people with a wide range of symptoms, stressful experiences and neurobiological profiles,” she explains, noting that symptoms such as disturbed mood, sleep and cognition often cut across anxiety, depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

“This is a growing area of precision medicine. It’s about moving beyond the confines of a diagnosis to focus on the individual in front of you.”

Understanding the Biology of Depression

Despite the fact that researchers have been studying depression for decades, we still don’t really understand all of the biological processes involved, which undermines effective treatments.

McQuaid’s research is best understood by zeroing in on a recent study she led that started with more than 500 Carleton students filling out questionnaires about their psychological health — a large and relevant sample, considering that about one-third of university-age Canadians are diagnosed with mental illnesses.

The students were asked about the specific anxiety or depression symptoms they were feeling. They were also asked about stressful early-life experiences.

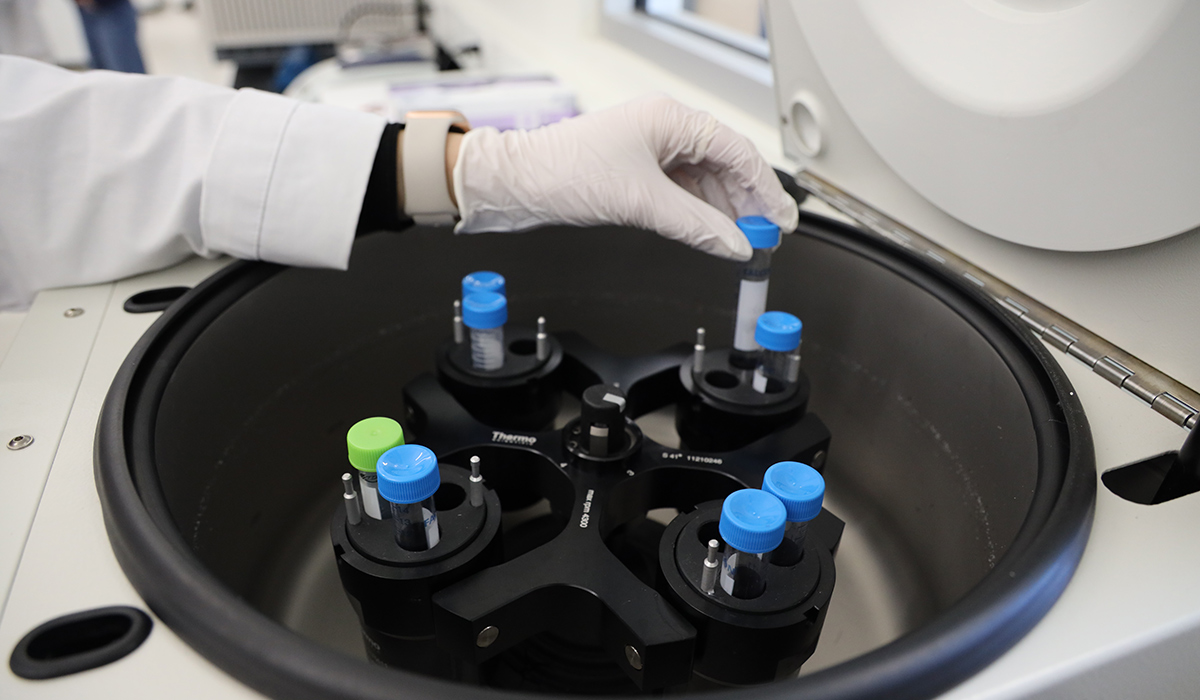

Then blood samples were collected, allowing the research team to look for inflammatory proteins in the blood — an immune system indicator of conditions like depression — and measure cortisol levels, a hormonal indicator of stress.

The results revealed six distinct “clusters,” from people who are happy and healthy to those with pronounced anxiety and depression.

“Some individuals predominantly showed anhedonia symptoms, or the inability to feel pleasure, while others had a predominantly physical form of depression, called neurovegetative depression,” says McQuaid.

“These people in particular reported a lot of increased sleep and appetite, and we could differentiate this group from others through their elevated inflammatory profiles.”

Biomarkers like inflammation could be one key to a tailored treatment response in the future, especially if they can be mapped onto specific clinical clusters of patients.

Researchers have known for a long time that individuals with depression can present elevated inflammation, but confirming precisely who does with a quick blood test could, down the road, lead a doctor to prescribe an anti-inflammatory medication for some patients alongside other treatments.

Next Steps for Treating Mental Illness

Findings from the Carleton student study are now published, and McQuaid is currently examining how early-life trauma fits into this story. Early-life adversity can get under the skin and have long-term consequences on mental health. This is important because individuals with early-life trauma respond more poorly to available treatments for depression.

Her graduate students are also currently doing an experiment to explore how the immune systems of people with various symptom profiles respond to challenges. Individuals face a lab stressor — a public speaking test — that elicits a biological and emotional response which can be seen in the activity of their white blood cells.

“These types of experiments give us a better sense of how specific people deal and cope with stress,” says McQuaid.

“They also give us insight into biological factors that can be used to identify risk for a disease, or to predict how somebody will respond to treatment.

“When you have a physical illness, you go to the doctor’s office and they collect biological data, and they can say your cholesterol is high and you may be at risk for heart disease. This is not the reality for mental illness, but in the future, it could be. That’s our goal.”