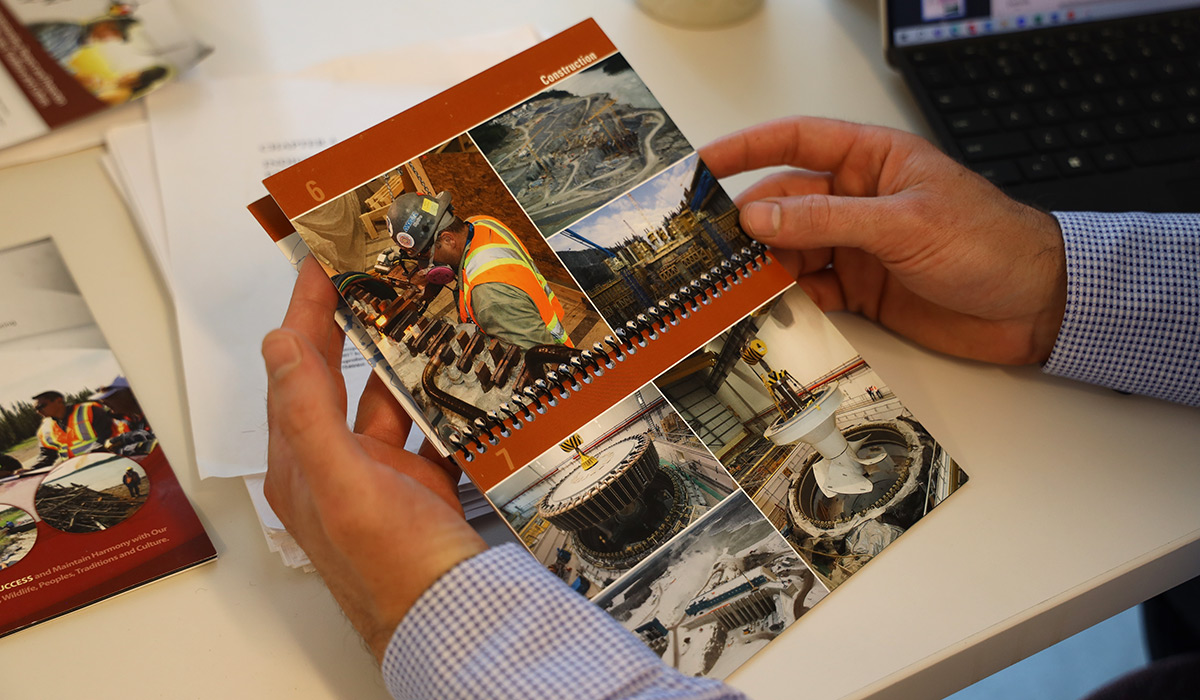

These decisions are based on geographical, economic and cultural factors — what makes sense for one community might not make sense for another — as well as the specific pros and cons of each venture.

Accordingly, the investment decisions made by Indigenous EcDev managers are “vastly more complicated” than the choices facing the mangers of publicly traded corporations,” says Carleton University finance researcher D’Arcy O’Farrell, a PhD student at the Sprott School of Business.

Conventional economic tools and theories, he adds, don’t provide much support.

Despite this challenge, it’s incumbent on academics to respond to the Calls to Action issued by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada in any way they can, according to Rick Colbourne, Carleton’s Associate Dean, Equity and Inclusive Communities and an Indigenous leadership and management researcher at Sprott who is O’Farrell’s co-supervisor.

This includes conducting research that explores Indigenous investment decision-making and making the results of this research available to members of the non-Indigenous business community to help foster understanding and partnership.

And it’s one of the reasons that Sprott, as part of a multi-year strategy led by a national non-profit called Indigenous Works and its Luminary initiative, is actively engaging in “economic reconciliation.” Indigenous EcDevs play a strong role in Canada’s economy, and Carleton recognizes the need to support their work.

More Than Conventional ROI

Existing investment theory holds that the only objective of investors is to make money, says O’Farrell. That assumption is a necessary simplification for a complicated problem, and it works quite well when the investor is, say, an individual saving for retirement.

But it’s not a good model for Indigenous EcDevs, whose managers invest for multiple objectives, exponentially increasingly the complexity of any analysis.

Another complication is the assumption that once an investment is made, the decision is locked in forever. This works fine, again, for a retirement portfolio.

“But when you’re investing in a business that you will actively manage,” O’Farrell says, “your initial outlay is only the beginning. Every day after that, there are decisions to be made which will impact the final outcome.”

All of these variables mean that, short of a powerful computer and precise mathematical model, Indigenous EcDev managers need to exercise a lot of judgement when making investment decisions. And that any insights gleaned from this process should be shared as part of the long journey toward reconciliation.

Increased Collaboration With Business Schools

Sprott was the first of dozens of university faculties to sign Indigenous Works’ Luminary charter, an effort to advance Indigenous innovation and grow economic well-being through increased collaboration among Indigenous businesses, communities and post-secondary institutions — in particular Canadian business schools, an academic discipline that has not historically been involved in Indigenous issues

“We’re looking for more long-term relationships and benefits coming out of research that resonates with Indigenous community needs, values and perspectives,” says Colbourne.

“Indigenous-led research can contribute to community socio-economic health and well-being by facilitating sovereignty, self-governance and self-determination. Business school research in Canada must be co-created and co-generated with Indigenous communities and EcDev corporations. It cannot be extractive — it has to be collaborative.”

Because this is a new direction for business schools, there are tremendous opportunities to explore, says Indigenous Works President and CEO Kelly Lendsay, who is also the founder and CEO of Luminary.

There’s a need for baseline information on Indigenous EcDevs and specific sectoral research in areas like agri-business, climate change and renewable energy systems.

Lendsay mentions the seaweed industry as an example. It’s a roughly $10 billion USD annual market in Asia, but Canada also has vast amounts of this sustainable food source on all three of our coastlines. With the right approach, Indigenous EcDevs in Arctic, Atlantic and Pacific communities could establish harvesting and export operations, providing local employment and enhancing food security in addition to bringing in revenue and building an Indigenous seaweed industry in Canada.

“Luminary’s research and innovation agenda can help Indigenous EcDevs develop new opportunities and make more informed business investments built on a foundation of solid research and innovation insights,” says Lendsay. “Indigenous EcDevs invest back into their communities, people, infrastructure and jobs.

“It’s nation building and it’s good for Canada and the world.”

By working together, Indigenous EcDevs and business schools both benefit, supporting the goals of the former and encouraging real-world impact for the latter. And by sharing the stories of successful EcDevs, the work of Sprott students like O’Farrell is demonstrating the possibilities and potential of Luminary — and could help inspire and support the next generation of Indigenous economic leaders.