Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s are devastating neurodegenerative diseases, primarily seen in those over the age of 65 and collectively affecting nearly one million Canadians. Where Parkinson’s affects the part of the brain that controls movement, Alzheimer’s targets memory and cognition. Both result in progressive cognitive and physical decline and eventually lead to the inability to function independently. The personal and financial costs of these diseases are severe and are set to worsen with the country’s aging population. By 2030, the number of Canadians with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s is estimated to double and the total annual health care costs are expected to reach up to $16.6 billion.

Tackling this combined health and economic challenge is difficult, but researchers in Carleton University’s Faculty of Engineering & Design believe that early detection of the diseases could be the solution.

“Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s can be managed much more effectively at their onset but there currently aren’t any clinical tests that can provide an early diagnosis,” says Ravi Prakash, a Electrical and Biomedical Engineer and lead researcher in Carleton’s Organic Sensors and Devices Lab.

“Individuals must have significant cognitive and physical deterioration before they can receive a definitive diagnosis.”

Addressing the Need for Non-Invasive Detection

The current testing for these diseases is also extremely onerous and requires invasive measures, with spinal taps being the most common method. This both delays diagnosis and can prevent individuals from going for testing in the first place.

Addressing this issue, Prakash’s team has created a non-invasive detection tool that indicates whether somebody is in the early stages of Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s. The tool only requires a saliva sample.

“With early intervention, the symptoms of these diseases can be reversed and medications and therapies can be put into place to prevent or slow further deterioration,” Prakash says.

“This could drastically decrease the strain on the health care system and loved ones and improve the quality of life for those diagnosed.”

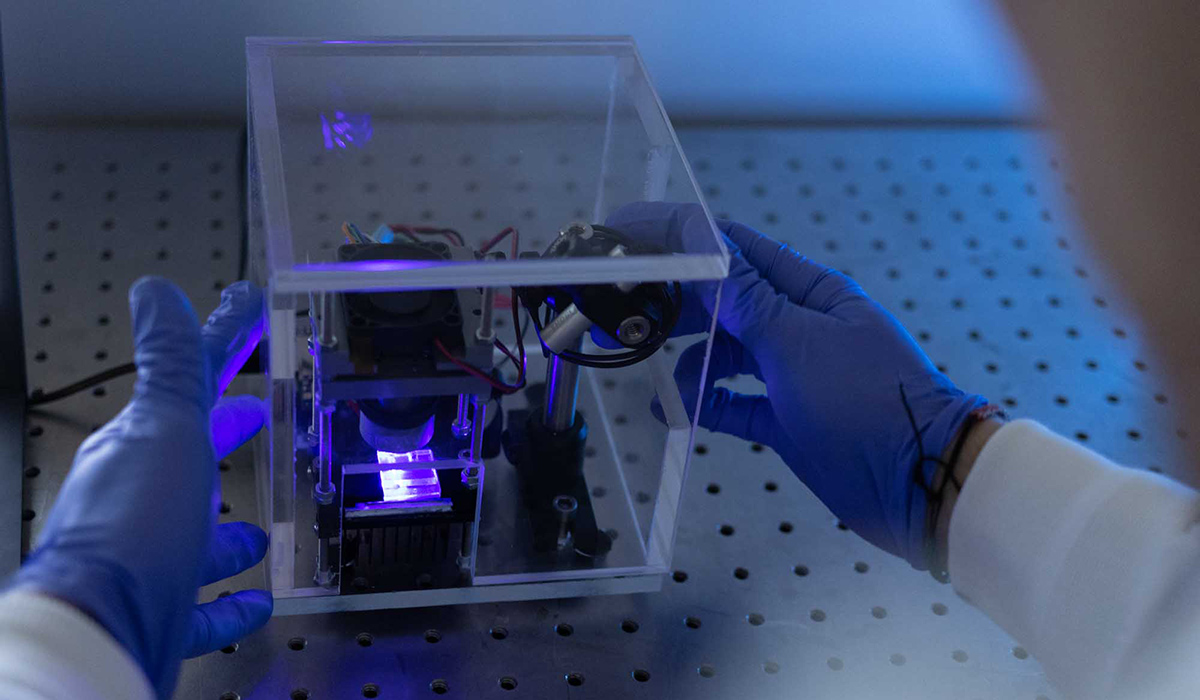

Created using a 3D printer, the groundbreaking device is about the size of the palm of a hand — making it both portable and cost-effective. It is made up of a circuit board loaded with disposable, single-use sensors that analyze saliva.

Currently, people have to go to a doctor with their symptoms, where they are put on a waiting list to see specialists and sent for a variety of tests that may not yield any results due to the stage of the disease. Prakash’s test will be able to indicate with high certainty if they have an early onset of Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s in that first visit to the doctor.

Health care providers will simply collect a saliva sample through a cheek swab or drool sampling, drop the sample into the sensing area of the tool, plug it into the USB port of a computer and get real-time results.

“The device detects biomarkers specific to these diseases directly through saliva,” Prakash explains.

“It only takes a few seconds to determine whether or not you have it.”

Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Biomarkers Found in Saliva

Biomarkers are biological molecules – such as proteins, antigens, and peptides – that are found in blood, tissue, or other bodily fluids. They provide signs of a normal or abnormal process, or of a condition or disease. Up until recently, it was believed that biomarkers for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s could only be found in blood or tissue. Recent work has indicated their presence, albeit on a smaller scale, in saliva.

“Saliva is the mirror of the body’s health,” says Prakash.

“The ability to non-invasively collect and screen saliva for target biomarkers has the potential to completely change the landscape for diagnostics.”

Prakash’s team was provided with the Parkinson’s biomarkers from Carleton researchers Maria DeRosa and Matthew Holahan from the university’s Faculty of Science, who are using the biomarkers to come up with treatments.

“Matt and I have been working for several years on a way to block the progression of Parkinson’s disease using a synthetic DNA molecule called an aptamer,” says DeRosa.

“It’s been so exciting to see how this same chemistry, applied to Ravi’s sensor platform, might also allow for early detection of the disease.”

Prakash says the early detection tool could also be utilized alongside treatment to monitor disease progression.

The device is currently in the process of commercial evaluation and advanced laboratory testing and is expected to begin clinical testing within the year. Prakash anticipates that the tool will eventually be used in doctor’s offices, hospitals and long-term care homes, and hopes that one day it will be available for people to use from the comfort of their own homes.

“It’s important to not only drive down costs, but also to create accessible testing right here in Canada,” says the Carleton researcher.

“People are suffering and our health care system is burdened. We need home-grown solutions. Canadians helping Canadians — that’s always been my motivation.”